CNC milling cost per hour matters most when you tie the rate to a clear scope of work and measurable cycle time. Many teams treat the hourly number as a simple price tag. However, the meaningful number is the total CNC Machining Cost to deliver accepted parts.. We separate hourly rates, setup, and risk drivers so we can budget, quote, and validate decisions with less rework.

Procurement managers want a defensible RFQ budget, while shop owners want a profitable machine rate. Engineers often want to change a feature and see the cost effect before releasing the drawing. We use one shared model that connects hourly rates to setups, verification, and outside services. This allows everyone to make decisions using the same definitions.

Define CNC milling cost per hour as two different numbers

CNC milling cost per hour has two meanings: internal machine operating cost and external billable shop rate. Internal operating cost covers what a shop spends to keep a mill producing. This includes depreciation, utilities, maintenance, and consumables.Internal operating cost typically excludes salaried engineering, administrative overhead, and corporate G&A, which are instead recovered in the shop’s billable rate. Billable shop rate adds skilled labor, engineering time, quality activities, and facility overhead, plus the margin needed to stay in business.

Internal cost per hour helps with shop planning, but it does not predict your invoice. Billable shop rate is what procurement sees, but it can hide setup and non-cutting labor if the quote is not itemized. We clarify which rate we are discussing before we compare CNC milling service suppliers or try to optimize a design.

A simple way to keep definitions clean is to separate “run cost” from “quote cost.” Run cost accumulates while the spindle produces chips. This includes power, coolant, and wear items that scale with run time. Some shops also include the on‑machine operator’s time in run cost, while off‑machine programming and administrative work are treated as separate cost buckets. Quote cost is what you pay to convert a drawing into accepted parts. It includes programming, setup, inspection, and the queue time created by outside processing.

What each definition usually includes

A cost model becomes stable when we map each line item to the correct bucket. Operating cost items usually include depreciation, planned maintenance, electricity, coolant, compressed air, and typical tooling wear that scales with run time. Quote and delivery items usually include programming, setup, probing cycles, first-article checks, deburring, packaging, shipping, and any documentation required for acceptance.

Business overhead items usually include facility rent, insurance, calibration, metrology, software licenses, and scheduling and administration. We use this mapping to prevent double counting. It also helps us spot quotes that hide setup and inspection inside a single blended rate.

Benchmarks for CNC milling hourly rates and why ranges conflict

CNC milling hourly rates span wide ranges because sources mix machine cost, shop rate, and part risk into one label. Some cost guides cite lower hourly figures for basic 3-axis milling when they describe equipment and operating cost assumptions. Other guides cite higher numbers because they describe customer-facing billing rates. These include engineering, inspection, and overhead.Public benchmarks for 3‑axis shop rates in the U.S. commonly fall in roughly the 40–120 USD per hour band depending on capability, region, and what is included, while 5‑axis milling often appears in the 100–200 USD per hour band or more for complex work.

A practical benchmark is to expect higher hourly rates as axis count, rigidity, and verification demand rise. Market guides commonly place 3-axis milling in a lower band, 4-axis milling in a mid band, and 5-axis milling in a higher band. Specialized or schedule-critical work goes beyond those bands. CNC Milling Jewelry often falls into this specialized category because fine details and surface-finish expectations can drive extra setup and verification time.We treat any “typical rate” as a starting hypothesis. Then we verify the real driver: how many paid hours it takes to produce accepted parts.

Hourly ranges also differ because some articles focus on “cost to run a CNC machine per hour,” not “shop billing rate per hour.” A run-cost breakdown may show only electricity, coolant, and tool wear. A billing rate may include the operator, CAM programming, and inspection resources. We prevent confusion by writing the rate type next to every number used in budgeting.

A realistic way to use published ranges

Published benchmarks are useful when we use them as guardrails, not as guarantees. We compare your quote to three reference bands: operating cost, basic billable shop rate, and high-risk billable shop rate. We then verify which band fits your tolerance, material, and delivery constraints.

What builds the hourly rate: machine, labor, tooling, and overhead

CNC milling hourly cost is a stack of costs that behave differently under load. Machine ownership cost depends on purchase price, expected life, financing, and annual spindle hours. Underutilization can quietly raise the true cost per hour. Many commercial shops plan around roughly 1,500–3,000 paid spindle hours per machine per year, but actual utilization varies widely with mix and shift pattern. Maintenance cost includes preventive checks, accuracy restoration, and unplanned downtime events that interrupt schedules.

A common machine-rate method spreads the machine purchase price across an expected life and a target number of annual cutting hours. Many cost guides assume thousands of annual usage hours for commercial CNC equipment. This means a shop that runs fewer billable hours must charge more per hour to recover the same investment. We ask one direct question before trusting any hourly figure: “How many paid spindle hours does the shop actually achieve per year?”

Utilities and shop consumables usually look small per hour, but they are predictable and must be counted. Many run-cost breakdowns model power usage in a single-digit to low double-digit kilowatt-per-hour band depending on machine class. For example, vertical milling centers may draw on the order of 10–20 kW at load, which often translates to only a few dollars per operating hour at typical North American power prices. They also include coolant and fluid costs that scale with run time. We include these items because they affect long runs and help explain why regions with cheaper power can price differently.

Tooling cost is not only the price of an end mill. It includes wear, breakage risk, toolholder condition, probing cycles, and time spent changing tools or re-touching offsets. We prevent tooling surprises by matching cutter geometry and coating to material. We also use realistic tool life assumptions for the cutting parameters.

Labor cost is the largest variable for many jobs because CNC milling is not only “machine time.” Labor includes programming, setup, first-article verification, in-process checks, deburring coordination, and final inspection. We separate operator time from engineering and inspection time because those hours do not scale the same way across batch sizes.

Overhead cost turns machine hours into a business that can deliver consistently. Overhead includes rent, insurance, calibration, metrology, software licenses, fixtures, and scheduling effort. Many cost guides also spread CAD/CAM and workflow software subscriptions across the machines and the billed hours. This explains why the same machine in a different shop can quote a different rate.

Run-cost elements that explain the “cost to operate” side

Run-cost models often include small, repeatable line items that are easy to overlook. We calculate electricity cost from estimated kW draw and local energy price. Many models add coolant, lubricants, and compressed air as fixed per-hour amounts. Tool wear is often modeled as a per-hour range because wear depends on material and cutting strategy. Some models allocate a per-hour budget for routine maintenance.

We use run-cost elements for two purposes. First, we test whether a supplier’s “very low hourly rate” is actually just the operating-cost view. Second, we use run-cost logic when a team is deciding whether to buy a machine and run parts internally.

Hidden steps that often belong in the cost model

Secondary steps can dominate cost even when milling time looks short. Deburring and surface finishing can be manual, outsourced, or integrated into the CNC cycle. Each path changes labor, quality risk, and queue time. Logistics costs such as packaging, special handling, shipping, and expedited transport can also swing totals for sensitive parts or urgent schedules.

Quality activity is another frequent blind spot. A quote that targets tight tolerances often requires probing, in-process checks, and final inspection time. This can exceed the cutting time on short-cycle parts. We verify the inspection plan early because it decides how many hours are truly “billable” for the job.

A single verification block we use before comparing hourly rates

Hourly rates become comparable only after we normalize assumptions.Many teams paste a short verification block into their RFQ template so each supplier responds on the same basis.

- We confirm whether the number is operating cost, shop rate, or a blended quote rate.

- We ask whether programming and setup are separated from cycle time.

- We ask how first-article inspection and in-process verification are handled.

- We ask what deburring, finishing, and outside services are included versus outsourced.

- We ask what packaging, shipping, and documentation are included in delivery.

We use these questions to prevent rate comparisons that reward hidden exclusions. We also use them to produce an RFQ scope that makes quotes comparable.

Job-level multipliers that change effective cost per hour

Setup and programming effort is the biggest multiplier for low-quantity work. A short cycle time does not help if the job needs complex fixturing, multiple work offsets, and extensive prove-out. We prevent setup shock by asking if the quoted rate includes setup hours as a separate line item or if setup is blended into the shop rate.

Part complexity raises cost because complexity raises time and risk. Multi-side access, deep pockets, thin walls, and feature relationships can force extra setups, longer tools, slower feeds, and more inspection. We compare complexity by the number of operations and setups, not by how “3D” a CAD model looks.

Tolerance and surface finish requirements change both cutting strategy and verification workload. Tighter tolerances can require smaller stepovers, controlled heat input, and more frequent checks. They can also increase scrap cost if stability is not managed. We decide on tolerances based on functional need, because cost grows quickly when requirements exceed the part’s real use case.

Material selection changes cycle time, tool life, and finishing needs. For example, CNC Milling for Wood can shift the cost drivers toward dust control, workholding, and surface finishing rather than tool wear in tough alloys.Soft, free-cutting materials can allow aggressive machining and long tool life. Difficult alloys force conservative cutting and stronger process control. We treat machinability as a planning variable and verify it with a brief process plan rather than a generic claim that harder materials cost more.

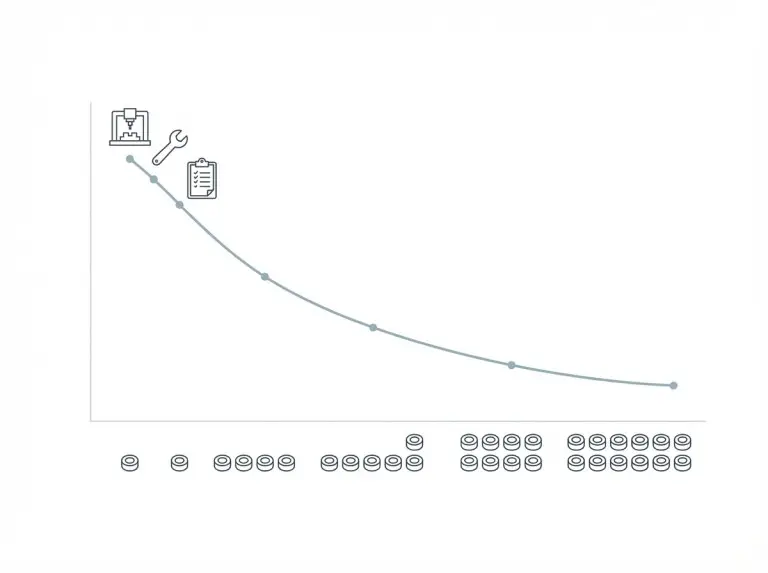

Batch size changes how fixed time is allocated. Setup, programming, and first-article inspection are mostly fixed per job. Cycle time scales with quantity. We compute cost per part by spreading fixed time across the planned quantity. Then we check whether lot size changes could reduce the effective cost without creating inventory risk.

Outside services can change both cost and lead time. Heat treating, plating, anodizing, and special coatings can introduce minimum lot charges, shipping legs, and queue time. These do not scale linearly with your quantity. We prevent surprises by listing outside services as explicit quote lines, not as a vague “finishing included” phrase.

Schedule pressure also changes the effective cost per hour. Expedited jobs can require overtime, interrupted schedules, and higher scrap risk during rushed setups. We decide whether speed or cost is the priority before we accept an expedited quote. The cost driver is often schedule disruption rather than machine capability.

A practical workflow to estimate and validate CNC milling hourly cost

A reliable estimate starts with separating fixed time from variable time. Fixed time includes programming, setup, first-article checks, and fixture prep. Variable time includes cycle time, tool changes, in-process checks, and deburring or finishing time that repeats per part. We use this separation because it matches how cost behaves when quantity changes.Before arguing about any hourly rate, we run a quick four-point check: what rate type each number represents, how many setups are assumed, how outside services are handled, and what annual paid spindle hours the machine-rate math is based on.

Step 1: List the operations and count the setups. The setup count determines how much non-cutting time you will buy, and it often predicts the inspection plan. We clarify whether the part can be completed in one setup. We also document what features must be held in the same setup to protect tolerance stack-up.

Step 2: Estimate cycle time with realistic feeds, speeds, and toolpaths. CAM time estimates are useful, but they can miss probing, tool changes, and conservative roughing strategies used for difficult materials. We verify cycle time by adding allowances for tool changes, chip clearing, and any in-process measurements required to hold tolerances.

Step 3: Build the hourly stack that matches the supplier’s reality. For internal planning, the stack can include depreciation, maintenance, power, coolant, and typical tooling wear. For supplier validation, the stack should include operator time, engineering time, inspection time, facility overhead, and the supplier’s profit margin structure.

Step 4: Compute the quote logic in a transparent form:

Total cost = (fixed hours × blended labor‑and‑overhead hourly rate) + (cycle hours × machine rate) + material + outside services.

This structure makes it clear when a lower hourly rate is offset by longer time, higher scrap risk, or larger outside service costs. We use this structure to compare quotes fairly across different process choices.

Step 5: Validate the estimate with “risk questions” instead of arguing about numbers. We ask how the supplier will fixture the part, how they will verify key dimensions, and what triggers rework or scrap. We prevent cost surprises by aligning the process plan, inspection plan, and finishing plan before work starts.

A worked example that shows why “hourly rate” is only one lever

A simple bracket can illustrate how fixed hours dominate small lots. Assume programming and setup consume 2.5 hours, first-article inspection consumes 0.5 hours, and the cycle time is 12 minutes per part. If the blended fixed-hour rate is $90 per hour and the machine cycle rate is $75 per hour, then fixed cost is $270 and per-part machining cost is $15.In this structure, the 90 USD/h blended rate covers programming, setup, and inspection labor plus overhead, while the 75 USD/h machine rate reflects operator and machine time during production.

Now compare quantity 5 versus quantity 50. At 5 parts, variable machining time is 1 hour and total labor and machine time cost is about $345, or about $69 per part before material and finishing. At 50 parts, variable machining time is 10 hours and total time cost is about $1,020, or about $20 per part before material and finishing.

This example is not a promise of real pricing. It shows the shape of the cost curve, because the curve is what matters when you pick a lot size. We use the same logic to explain why a higher hourly rate can still be cheaper if it reduces setups or cycle time substantially.

Why job costing discipline changes quote quality

Accurate job costing depends on measuring what actually happens on the floor. Shops that track setup time, tool change time, deburring effort, and inspection effort can quote jobs more consistently. We encourage teams to ask suppliers whether they measure these steps. Measurement discipline often predicts whether the quote will match the final invoice.

Job costing also improves internal decisions. When a shop knows the real cost drivers, it can decide where automation helps most. This might include pallet systems, probing routines, or integrated deburring strategies. We treat job costing as a practical risk-reduction tool, not as a finance exercise.

Cost levers that lower total spend without cutting quality

Cost reduction works best when we change the drivers of time and risk, not when we chase the lowest hourly rate. A common win is geometry simplification that reduces setups, tool changes, and inspection steps. Typical edits include enlarging internal radii so they are at least 1.5× the cutter diameter, standardizing hole sizes to common drill and reamer sets, and avoiding unnecessarily deep narrow slots.

Tool reach and rigidity are cost levers that designers often overlook. Long-reach tools chatter, require slower feeds, and reduce tool life. This increases both cycle time and tooling cost. We prevent long-reach penalties by adjusting feature depth, adding access, or allowing a larger internal radius that permits a stiffer cutter.

Material and finish choices can be tuned to performance needs. Choosing a more machinable alloy, relaxing a cosmetic finish requirement, or limiting tight tolerances to functional features can reduce cycle time. We verify these choices with a brief “function-to-feature” review so we do not trade cost for failure risk.

Process planning can also reduce paid hours. Modular fixturing, repeatable probing routines, and stable tool libraries reduce setup time. Automation can reduce operator touch time during long runs. We compare options such as running a faster 5-axis strategy versus using multiple 3-axis setups. A CNC Milling and Turning Machine can consolidate milling and turning operations into one setup, reducing paid hours, handling, and tolerance stack-up risk.The lowest shop rate is not always the lowest total cost.

Finishing and deburring choices deserve explicit attention. Integrating deburring or finishing steps into the CNC process can reduce manual labor and variability. Outsourcing can add transportation, queue time, and damage risk. We decide the finishing route based on part geometry, surface requirements, and the acceptable queue risk for your schedule.

Procurement strategy can reduce cost without touching the drawing. Consolidating similar parts into fewer purchase orders can reduce repeated setup charges. Adjusting reorder cadence can also reduce “one-off” setup repetition, as long as inventory risk stays acceptable.

A short checklist for quote-ready inputs

Quote accuracy improves when we lock the scope and the verification plan up front.

- Drawing or 3D model with revision control

- Material and condition requirement

- Critical tolerances and datums that drive the inspection plan

- Surface finish and post-process requirements for specific faces

- Quantity and expected reorder pattern

- Delivery timing and any special handling constraints

We use these inputs to prevent hidden costs, especially for setup-heavy prototypes and tolerance-driven parts.

Conclusion

At Yonglihao Machinery, we understand that CNC milling hourly costs only truly reflect the project’s total cost when combined with a clear process plan and inspection scope. That’s why we always calculate operating costs, shop floor rates, and specific project cost factors separately. This ensures your budget decisions are based on the total cost of delivering qualified final parts, not just a single hourly rate.

Before production begins, we’ll work with you to verify all details in the quotation, such as clamping times, estimated machining cycles, and finishing steps, to eliminate any unexpected costs.

**To provide you with an accurate quotation and production plan, we require the following information:**

– Part drawings or 3D models (please specify version number)

– Material grade and condition

– Critical tolerances, datums, and surface finish requirements

– Order quantity, preferred batch size, and estimated annual demand

– Post-processing steps, such as deburring, anodizing, heat treatment, or coating

– Delivery time, packaging requirements, and required inspection documents

With our extensive CNC machining experience, we can review your parts and provide process routes and tooling solutions that meet your tolerance and production needs. We can also help you validate inspection plans and identify potential risks, making your RFQ (Request for Quotation) process clearer and more efficient.

FAQ

What is a typical CNC milling cost per hour for a 3-axis machine?

Typical 3-axis CNC milling billing rates often fall in a broad middle band, but the right number depends on what the quote includes. Some sources cite lower 3-axis figures when describing machine operating cost. Supplier-facing quotes usually include labor, overhead, and quality work. We validate the rate by checking whether programming, setup, and first-article inspection are separated or blended.

How much more does 5-axis milling cost per hour?

5-axis milling usually costs more per hour because machine ownership, maintenance, and verification needs are higher. The higher hourly rate can still reduce total cost if it cuts setups and reduces handling risk. We compare 5-axis and multi-setup 3-axis plans by total paid hours, not by the hourly headline.

Why do some sources show very low hourly costs?

Low hourly figures often describe internal operating cost or a simplified machine-rate calculation. Customer billing rates typically include labor, engineering, inspection, overhead, and margin, so they are higher. We separate these definitions before using any benchmark in a budget.

Do setup fees matter more than hourly rate for prototypes?

Setup and programming usually dominate prototype cost because quantity is small and fixed hours cannot be spread. A low hourly rate does not help if setup takes many hours or if repeated prove-out is needed. We prevent prototype overruns by focusing on setup reduction and on early DFM feedback.

What hidden costs should procurement watch for in CNC milling quotes?

Hidden costs often come from finishing, deburring, outsourcing, transportation, and special handling. Inspection intensity, rework risk, and scrap allowances can also change total cost even when the hourly rate looks stable. We ask for clarity on these items before approving a supplier.

How can we estimate the cost to run our own CNC mill per hour?

In-house operating cost estimation starts with annual spindle hours and the machine’s total ownership cost. Power, coolant, and wear items add predictable per-hour costs. Labor and quality resources determine whether your internal shop rate matches outside quotes. We can help you separate these buckets so you can compare “make versus buy” decisions fairly.