When you design a metal part, the process choice sets your cost, lead time, and quality ceiling. At Yonglihao Machinery, we support both CNC machining and metal casting for real production. We see the same pattern. The best method matches your tolerances, geometry, and volume.

Casting forms shape by solidification in a mold. Machining forms shape by removing material from solid stock. Both can produce excellent parts. But they solve different problems.

This guide helps you pick the right route for your part. We focus on the differences that change decisions. These include tolerances, surface finish, geometry, volume, lead time, cost structure, and quality risks.

When to Use Casting vs Machining vs Cast-Then-Machine?

Casting works best when you need complex geometry at scale. It shines with internal cavities and thick-to-thin transitions. Near-net shapes cut machining time. Once tooling is ready, cost per part drops as volume rises.

Machining works best when precision and speed matter more than per-part cost. It fits prototypes and small batches. It suits parts with tight tolerances and controlled surface finish. It also fits projects that change often. You can update a program faster than revise molds.

Cast-then-machine often proves most practical for industrial parts. You cast the bulk geometry to save material and cycle time. Then you machine only the critical features. This approach fits housings, valve bodies, and parts with sealing faces, bores, or bearing seats.

Remember one rule. Cast for shape and volume. Machine for accuracy. Combine them when you need both.

Casting vs Machining Basics

Casting creates a part by pouring molten metal into a mold. You let it solidify. The mold defines the main geometry. You can form shapes that cost a lot to carve from solid stock. This includes internal passages with cores.

Machining creates a part by removing material from a billet, plate, or bar. Cutting tools follow a controlled path. They reach the final geometry. The key advantage is predictable accuracy. It also gives stable surface quality across critical features.

For both methods, clarify a few inputs early. This is the fastest way to choose. We start with material, quantity, and the part’s critical features. Then we confirm tolerance and surface finish targets. With those inputs, the process choice becomes less subjective.

What Is Casting?

Casting turns molten metal into a solid part inside a mold. People use it for parts with complex shapes. It fits internal cavities or large sizes. It can be the cheapest route for high volumes of the same design.

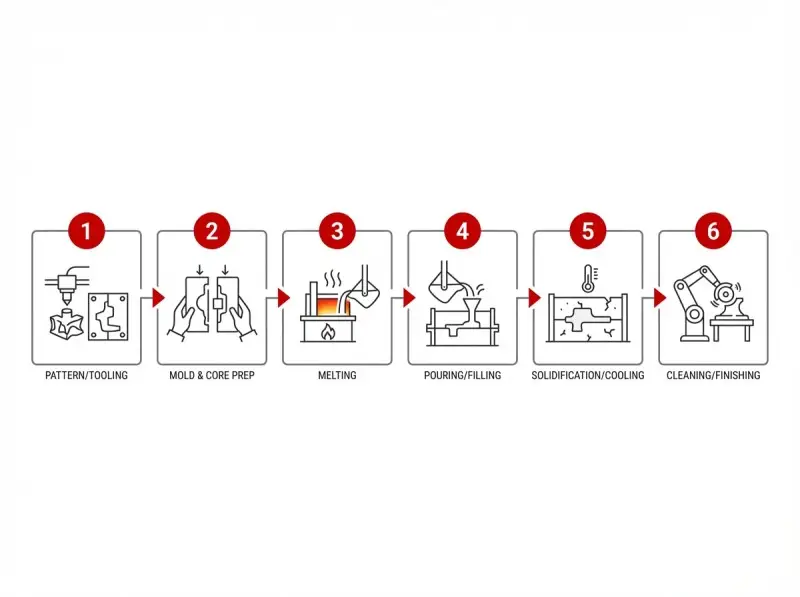

Casting workflow: mold, pour, solidify, finish.

Most casting projects follow a similar workflow. You start with a pattern or tooling concept. You prepare the mold and any cores for internal features. Then metal melts. You pour or inject it into the cavity.

After fill, solidification happens as the metal cools. The cooling stage decides many quality outcomes. If cooling is uneven, you see shrinkage, warping, or internal voids. Once the part solidifies, you remove it. You clean it. You prepare it for any finishing.

Typical post-processing after casting

Many cast parts need secondary work before they ship. Common steps include trimming gates and risers. You deburr. You blast. You clean the surface. Heat treatment may stabilize properties. It can improve strength. This depends on alloy and application.

Light machining is common, even when the part is cast. It is faster to cast the bulk. Then machine a few faces and bores. This beats machining the entire part from solid stock.

Common materials for casting

People use casting for metals that melt and pour with stable behavior. In production, material choice affects fluidity. It affects shrinkage and defect risk. At Yonglihao Machinery, we support casting with stainless steel. We use steel alloys, carbon steel, and aluminum. This bases on application needs.

Choose material for performance first. Then confirm the casting route achieves required quality. It must achieve repeatability. If the part has critical sealing or bearing features, plan to machine those surfaces. Do this even if the main body is cast.

What Is Machining?

Machining removes material from solid stock. It achieves the final shape. CNC machining uses computer control. It moves tools and workholding with repeatability. This makes machining a default choice for tight tolerances. It gives stable surface finish.

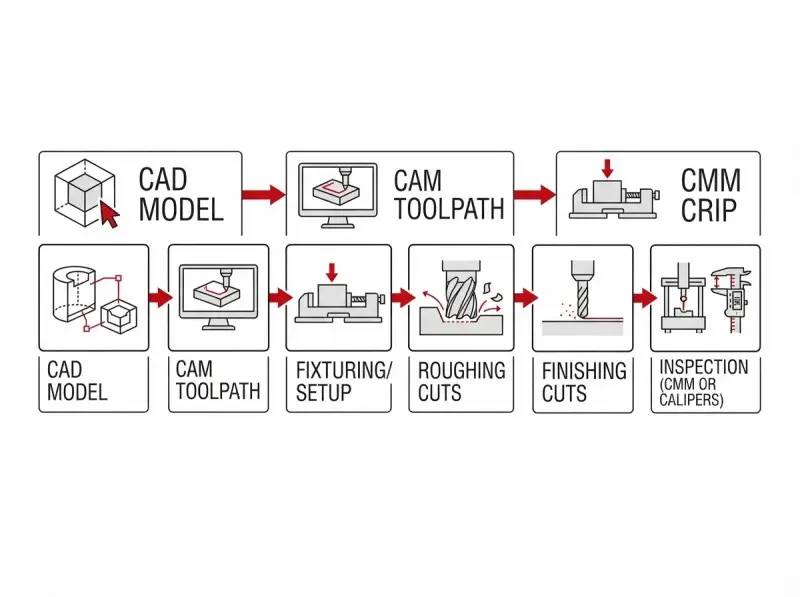

Machining workflow: program, setup, remove material, inspect.

Most CNC projects start with a CAD model. You create toolpaths. You design fixtures or workholding. The part cuts in stages. This manages accuracy, tool load, and surface quality.

Inspection is key in machining. You verify critical dimensions during the run. You confirm final acceptance features at the end. This delivers consistent results. It works across prototypes and short-to-mid production runs.

Common machining operations you’ll actually use

CNC milling fits prismatic parts, pockets, slots, and 3D surfaces. It suits brackets, plates, housings, and complex external geometry. Milling supports flatness. It controls position for features like bolt patterns.

CNC turning fits rotational parts. It suits shafts, bushings, threads, and concentric diameters. Turning delivers excellent roundness. It gives repeatable diameters when fixturing is stable.

Drilling and reaming create holes with controlled size and finish. Grinding pushes surface finish or dimensional control further. It works on hardened parts. These operations support the last step of making it fit for critical interfaces.

Common materials for machining

Machining works with a wide range of materials. Metals are most common for industrial parts. But plastics, composites, and other materials can be machined. This happens when the application requires them. Machinability affects tool choice. It affects feeds, speeds, and achievable finish.

Match the process to the part’s most demanding features. If the part needs tight tolerances on multiple faces or bores, machining provides a direct path. If the part is mostly non-critical geometry with a few critical interfaces, cast-then-machine can cut cost. It keeps function.

Main Types and Typical Uses

Different casting and machining methods exist. No single method fits every part. Understand what each method produces best.

Sand casting

People choose sand casting for large components. It fits flexible design changes. The molds are expendable. This reduces tooling commitment compared to permanent dies. It fits when size is large. Geometry is complex. Tolerances can finish by secondary operations where needed.

Expect a rougher as-cast surface. Expect wider dimensional variability than precision methods. When sand casting fits functional parts, machine sealing faces. Machine bores and mounting interfaces.

Die casting

Die casting fits high-volume production. It uses metal dies. It offers strong repeatability. It gives efficient cycle times once the die validates. People use it for nonferrous parts. Output speed and consistent shape matter.

Die casting produces good surface finish. It gives fine external detail. But initial tooling investment is higher. It works best when volume and design stability justify that tooling.

Investment casting

People use investment casting for intricate shapes. It gives finer surface finish than many casting routes. It fits when geometry is detailed. Machining would be difficult or wasteful. It fits when part complexity and near-net shape cut overall processing.

Even with investment casting, critical interfaces may need machining. You gain shape capability. Then you lock final dimensions where it matters.

Pressure or squeeze casting

Pressure or squeeze casting applies force during solidification. This improves density. It reduces some defect risks. Consider it when mechanical performance demands more. Minimize porosity compared with conventional casting routes.

This method fits structural parts. Performance and consistency are priorities. Design acceptance around critical machined features. Do this if the part must mate, seal, or align with other components.

CNC milling

CNC milling handles complex external geometry. It handles multi-feature parts. It supports pockets, slots, and shaped surfaces with high repeatability. It fits prototypes. You change geometry by updating the program.

Milling fits when the part has multiple critical features that relate. Hole patterns, datums, and interface faces control in one plan.

CNC turning

CNC turning fits parts where concentricity and roundness drive function. Shafts, sleeves, threaded features, and stepped diameters are typical. Turning combines with other operations. This happens when parts need both rotational and prismatic features.

If the part’s key requirement is a controlled diameter, turning is efficient. If the part needs flats, pockets, or side features, combine turning with milling where needed.

Key Differences That Decide the Method

Compare the right dimensions. Most process debates become simple.

Tolerances and surface finish

Machining leads to tight tolerances. It controls surface finish. If your part requires tight fits, alignment, or predictable sealing, machine those features.

Casting can be accurate for many applications. This holds with precise methods. But casting accuracy depends on method, alloy, and part geometry. When tolerances are strict, cast parts need machining on critical features.

Geometry feasibility

Casting creates internal cavities. It makes complex shapes efficiently. Cores and mold design allow shapes hard to machine from solid. Many housings and fluid-handling bodies are cast.

Machining limits by tool access and workholding. Deep internal passages may require multi-step setups. They may be impractical. If geometry blocks tools, casting or hybrid becomes practical.

Volume, lead time, and scalability

Machining starts quickly. For prototypes and small batches, go from CAD to part with minimal setup. Machining dominates early-stage development.

Casting needs tooling and validation time. But it scales better for high volumes. Once tooling proves, production cycles become efficient. If demand is stable and high, casting reduces per-part cost.

Cost structure and material utilization

Casting has higher upfront tooling cost. Per-part cost lowers at higher volumes. Near-net shape improves material utilization. You avoid paying to remove large stock amounts.

Machining has lower upfront tooling. But per-part cost includes machine time and material waste. If a part removes a large percentage of starting stock, cost rises.

Think about cost this way. If design is stable and volumes are high, casting amortizes tooling. It wins on unit cost. If design changes or quantities are low, machining wins on speed and flexibility.

Quality risks

Casting quality risks tie to solidification. Porosity, shrinkage, warping, and surface irregularities can appear. This happens if process control and design misalign. These risks mean you must plan quality control. Plan finish strategy.

Machining avoids solidification defects. You start with solid stock. Main risks are tool marks. Distortion from clamping. Variation from tool wear if controls are weak. Manage these through process planning and inspection.

When your part cannot tolerate internal voids in critical regions, hybrid makes sense. Cast for shape. Machine away surfaces where defects matter. Control acceptance on machined datums.

How to Choose?

A good framework turns a drawing into a process route. We use a simple sequence. It works for prototypes and production.

- Step 1: Start by marking what must work. Ignore what looks complex. Sealing faces control success. Bearing bores do too. Alignment datums and threaded interfaces matter. If these are critical, plan to machine them. Or design them for machining after casting.

- Step 2: Split the part into two zones. Zone A includes features that drive function and assembly. Zone B includes cosmetic or non-critical features.This split avoids overpaying for precision everywhere. It defines where casting works. It shows where machining must apply.

- Step 3: Choose material based on performance. Then confirm feasibility. Some alloys cast easy but machine hard. Others machine well but cast with inconsistent quality.If material is fixed, adjust process route. If process route is fixed, adjust material or acceptance criteria. Make the decision explicit.

- Step 4: If you need parts quickly, machining is best. It fits design changes. If design is stable and demand is high, casting attracts.Avoid rigid volume thresholds. Break-even depends on part size. It depends on complexity, material cost, and quality needs. Estimate total cost and risk across lifecycle. Include prototype, pilot, and production.

- Step 5: Base the decision on critical features and expected volume. If casting, define machining allowance. Specify which features machine to final size. If machining, confirm geometry is accessible. Confirm material waste is acceptable.

If hybrid, be precise about scope. Hybrid works best when you cast bulk geometry. Machine only interfaces that control function. This reduces cost. It keeps precision.

| Decision Driver | Casting | Machining | Cast-Then-Machine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best for | Complex shapes, cavities, high volume | Tight tolerances, prototypes, controlled finish | Complex shape + tight critical features |

| Upfront effort | Tooling and validation | Programming and fixturing | Tooling + defined machining plan |

| Per-part cost at scale | Low | Higher | Often optimized |

| Tolerance/finish | Depends on method; often needs finishing | Strong and predictable | Machined where it matters |

| Typical risk | Porosity/shrinkage/warpage | Tool access, cycle time, scrap | Process planning and allowances |

Conclusion

If you need speed, flexibility, and tight tolerances, machine. It is the fastest path to a passing part. If you need complex geometry and large quantities, cast. It delivers best unit economics once tooling validates. If you need both shape complexity and precision interfaces, cast-then-machine is practical.

At Yonglihao Machinery, a die casting company, we help you choose. We base it on the part’s critical features, material, quantity, and acceptance criteria. Share your CAD model. Share target material, expected volume, and features that control function. We recommend a process route. It fits your timeline and quality needs.

FAQ

Which is cheaper, casting or machining?

Casting is cheaper per part at higher volumes. This happens after tooling amortizes. Machining is cheaper for prototypes and small batches. No mold investment. True break-even depends on part complexity. It depends on material cost. It depends on stock removed in machining.

Which is more accurate, casting or machining?

Machining is more accurate for tight tolerances. It controls finishes. Casting accuracy depends on method and design. Many cast parts machine critical interfaces. If design has tight fits or sealing, plan machining on those features.

When does “cast-then-machine” make the most sense?

Use cast-then-machine for main shape from casting. Use machining for features that control assembly or performance. This fits housings, valve bodies, and parts with bores. It fits sealing faces and bearing seats. It reduces waste and cost. It keeps precision where it matters.

What casting defects should I plan for, and how do they affect acceptance?

Typical risks include porosity and shrinkage voids. Warping and surface irregularities too. These matter near sealing faces. They matter in bores and load-bearing interfaces. Cast near-net shape. Machine critical features to remove defects. Control final dimensions.

What features are hard to machine, and what’s the practical workaround?

Enclosed cavities are difficult. Deep internal passages too. Features with poor tool access cost more. Use casting to form internal geometry. Then machine accessible critical interfaces. Redesign for tool access in some cases. This reduces complexity without changing function.