Milling removes material with a rotating cutter. The tool you choose decides speed, stability, and the features you can make. In most shops, the choice comes down to two families: face mills and end mills.

Here is the core rule. Use a face mill to machine large flat faces fast. Use an end mill to create slots, pockets, shoulders, profiles, and 3D features with control. End mills can sometimes face a surface, but a face mill cannot replace an end mill for feature machining.

At Yonglihao Machinery, we support CNC milling service for prototypes and production parts. When clients ask which tool they should pick, we start from the part geometry and the machine’s stiffness. Then we match the cutter family to the job.

What Is a Face Mill and What Is an End Mill?

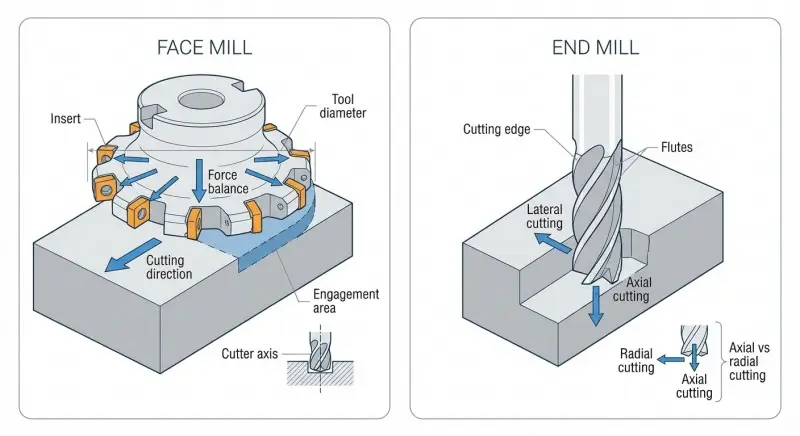

A face mill is a cutter built to machine a surface that is perpendicular to the spindle axis. It uses multiple inserts or cutting edges to remove material across a wide path. That is why it is the first choice for broad, flat faces and prep cuts.

Face milling operation typically places the workpiece so the target face is normal to the tool axis. You clamp the part rigidly, select a stable spindle speed and feed, and sweep the cutter across the surface. Many faces can be produced in one or a few passes, depending on width and stock allowance.

End mill is a cutter with cutting edges on the end and along the flutes on the sides. It can cut laterally and also engage axially for plunging or ramping, depending on the tool style. This makes it the go-to choice for pockets, slots, shoulders, contours, and die features.

End milling keeps the tool engaged in a smaller area than face milling. That improves access and feature control, but it also means forces are concentrated on a smaller cutter. Tool deflection and vibration become the limits faster, especially with long stick-out.

Tool Geometry and Cutting Behavior

The real difference is not just milling versus milling. It is where the cutting edges are and how much of the tool engages the work at once. That drives cutting direction, force balance, chip thickness, heat, and stability.

A face mill carries inserts around a large diameter. It engages a wide area, spreads load across multiple edges, and tends to run with balanced forces when set correctly. This helps stability on large faces and improves productivity when you need to remove stock quickly.

An end mill has a smaller diameter and flutes that cut on the side and at the tip. It can move into tight areas and create depth features. That versatility comes with sensitivity to stick-out, tool rigidity, and chip evacuation, especially in deep pockets and narrow slots.

Tool edge form matters too. Face mills usually use replaceable inserts, which supports consistent performance and easy maintenance. End mills are often solid tools, and they may require regrinding or replacement when worn, depending on your tooling strategy.

If you only remember one geometry point, remember this. Face mills are built to face surfaces. End mills are built to feature details. That one line prevents most wrong tool choices.

Face Mill vs. End Mill: Performance Comparison Checklist

If you want a clean decision, compare both tools using the same checklist. The goal is not to rank them. The goal is to match the tool’s strength to your part’s requirement.

Below is a compact comparison you can use during process planning.

| Decision factor | Face mill (typical strength) | End mill (typical strength) |

|---|---|---|

| Best output | Large flat faces, prep and finishing passes | Pockets, slots, shoulders, profiles, contours |

| Material removal tendency | Higher on wide faces | Lower on broad faces, better for features |

| Surface finish tendency | Very good flatness and uniformity on faces | Very good on features and contours, depends on tool type |

| Access | Needs open face and clearance | Reaches tight spaces and internal features |

| Depth behavior | Best for shallow-to-moderate face cuts | Can cut deeper features, limited by rigidity and chip evacuation |

| Rigidity sensitivity | Needs a rigid setup due to cutter diameter and forces | Sensitive to stick-out and deflection, especially in deep pockets |

| Typical tool form | Inserted cutters (easy edge replacement) | Solid or inserted end mills (many geometries) |

This table is a guide, not a law. A small end mill can machine a small face. A face mill can create shallow pockets if geometry allows. But the best fit stays consistent.

When to Use Each Tool?

If the part has a large face that drives assembly, sealing, or alignment, you should bias toward face milling. You get faster stock removal and more predictable flatness. You also reduce cycle time when there is a lot of area to cover.

Use a face mill when your goal is to level a surface, remove scale, or prepare a datum face before feature work. This is common on frames, machine bases, engine-like housings, and fixture plates. The face milled surface becomes the reference for the rest of the program.

Choose an end mill when the part requires internal geometry. Slots, pockets, shoulders, keyways, and 2.5D or 3D contours are end mill territory. The tool can cut on the sidewalls, step down in Z, and follow a profile path accurately.

End milling is also the better choice when the surface is broken by existing features. A face mill needs clearance and a clean sweep area. If the face has bosses, ribs, or holes near the cut path, an end mill gives you safer access and better control.

In many real jobs, both tools belong in the same program. Face mill the datum face first, then end mill features, then finish critical faces or bosses. That sequence reduces stack-up error because later cuts reference a verified flat surface.

At Yonglihao Machinery, we often plan the job like this: create stable datums early, then cut features with controlled engagement, then finish critical interfaces last. It keeps inspection predictable.

Setup Factors That Change the Result

Machine rigidity is not a footnote. It decides whether your cut is smooth or noisy, and whether your surface is stable or wavy. Face milling can generate high forces due to wide engagement, so a rigid spindle and solid fixturing matter.

End milling is more sensitive to tool deflection. Smaller diameter tools and long stick-out behave like a spring. If the tool bends, you lose size, wall straightness, and surface quality. This is why deep pockets and thin walls need extra planning.

Workholding is the second big lever. A face mill can push the work if clamping is weak, which ruins flatness. End mills can chatter or pull chips into the cut if the part vibrates, which damages edges and leaves marks.

Material choice changes chip formation and heat. Aluminum can build up on edges without good chip evacuation and coolant strategy. Hard steels increase wear and require stable engagement to avoid chipping. The correct tool family still applies, but the margin for error shrinks.

Chip evacuation is often the hidden limit in end milling. Deep pockets and narrow slots trap chips, raise heat, and cause re-cutting. If chips cannot leave, your tool life collapses and your finish degrades fast.

If you are choosing between faster and safer, choose stable first. A stable cut lets you raise feed later. An unstable cut never becomes efficient.

Common Problems and Quick Fixes

Chatter or vibration on a face-milled surface usually means poor rigidity, wrong engagement, or a dull edge. Reduce overhang, improve clamping, and check insert condition. If the surface shows repeating waves, stabilize first before chasing speed.

Tool breakage during end milling often comes from excessive stick-out or chip packing. Shorten the tool projection, open the pocket strategy, and improve chip evacuation. A tool that cannot clear chips is running into its own waste.

Poor surface finish in face milling can come from uneven inserts, incorrect tool setup, or inconsistent feed. Verify insert seating, use consistent feed across the face, and avoid stopping on the surface. A stop mark is usually a process control issue, not a material problem.

Size errors on walls or slots often point to deflection in end milling. Reduce radial engagement, use a more rigid tool, or split roughing and finishing. A light finish pass with stable engagement often fixes wall straightness.

Burning, discoloration, or warped areas can happen when heat is not managed. Improve coolant delivery and avoid re-cutting chips. In hard materials, unstable engagement can spike heat locally and damage the edge quickly.

These fixes stay within the same principle. Control rigidity, engagement, and chip flow. The cutter family works when the system supports it.

Conclusion

A face mill is the best tool for large, open faces where productivity and flatness matter most. An end mill is the best tool for features where access, depth, and contour control decide the result. End mills can sometimes face small areas, but face mills cannot replace end mills for feature machining.

If you want a simple workflow, do it in this order. Establish a flat datum face, then machine features with end mills, then finish critical interfaces last. At Yonglihao Machinery, we apply this logic across our cnc machining services to keep cycle time, accuracy, and surface quality predictable for both prototypes and production parts.

FAQ

Can you face mill with an end mill?

Yes, an end mill can machine a flat face, especially on small areas. It is a practical choice when clearance is limited or the face is interrupted by features. It is usually slower than a face mill on large open faces.

Can a face mill do end milling tasks like slots and pockets?

In most cases, no. A face mill is built to sweep open faces, not to create narrow internal geometry. It may create shallow recesses when geometry is open, but it cannot replace an end mill for pockets, slots, shoulders, and profiles.

What is the most significant difference between a face mill and an end mill?

The most significant difference is cutting edge placement and engagement. Face mills cut primarily across the face with wide engagement. End mills cut on the end and sides, so they can create depth features and complex paths.

Which one gives a better surface finish?

On large flat faces, a face mill usually gives more uniform flatness and a cleaner face finish. On features like pockets, contours, and radii, an end mill is the right tool and can deliver excellent finish when engagement and chip evacuation are controlled.

How do I choose quickly between face milling and end milling?

Choose a face mill when the main goal is a large flat face and fast stock removal. Choose an end mill when the main goal is geometry: slots, pockets, shoulders, profiles, or contours. If the job has both, face mill the datum first, then end mill features.