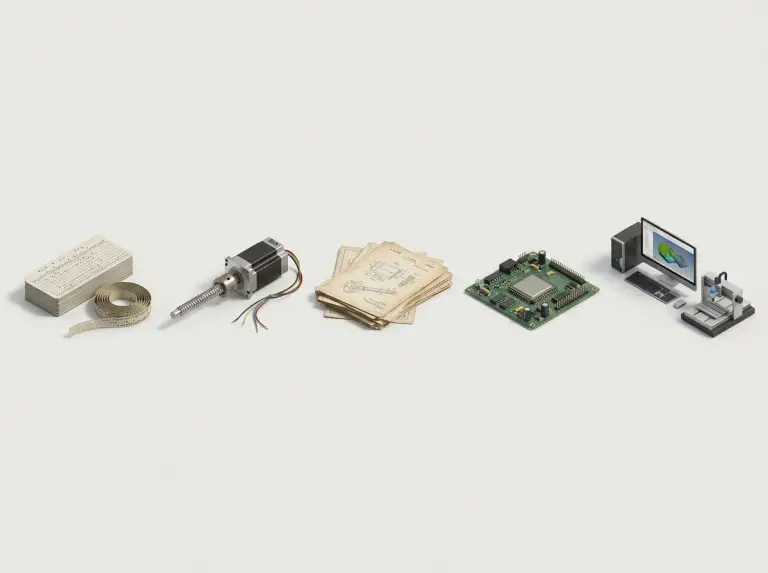

CNC milling history explains how coordinate-based control turned milling from a manual skill into repeatable, programmable motion. The story of CNC milling overlaps with CNC Machining History, but milling is the best lens because early numerical control milestones were demonstrated on milling platforms. This article aims to map the major transitions without drifting into unrelated machine-tool history.

Modern shops often see CNC milling as a finished system that “just runs code.” However, CNC milling became practical only after solving several key constraints, including motion control, program storage, and editing workflows. A clear timeline helps readers avoid mixing up NC milestones, CNC controller milestones, and CAD/CAM milestones.

CNC Milling Scope and Core Terms

CNC milling history is easier to understand when you separate CNC milling, CNC machining, and numerical control as distinct terms. CNC milling removes material with a rotating multi-point cutter while a controller drives axis motion. CNC machining is broader, commonly including both milling and turning under computer control.

Numerical Control (NC) refers to machine motion driven by numerical instructions without needing a computer at the machine. Early NC used punched media and hardware logic to follow coordinate steps. Computer Numerical Control (CNC) adds a computer-based controller that stores, edits, and executes programs with greater flexibility.

The CNC milling timeline also uses a few recurring system terms. The Machine Control Unit is the controller that interprets a program and commands the axis drives. Direct Numerical Control is a shop-floor system where a central computer sends programs to multiple machines, which was important when computers were scarce and expensive.

Common CNC Milling Misconceptions

People often misunderstand CNC milling history because the word “computer” makes them assume full digital control existed from the start. Early milestones are often described as coordinate-driven machining using punched cards or tape, which is not the same as a modern CNC controller. A clean timeline must acknowledge that sources use the “NC” and “CNC” labels differently.

A second misconception treats “the first CNC machine” as a single, universally agreed-upon artifact. Many accounts point to early aerospace-driven projects that used coordinate calculation and controlled motion on milling equipment. Later, they cite a demonstrated NC milling machine as a milestone. Readers should view “first” claims as shorthand for a family of early prototypes, not a single commercial product.

A third misconception assumes the leap to CNC was only about precision. CNC milling adoption also depended on practical shop workflows, such as program storage, edits, and setup repeatability. The controller and programming workflow changed how milling work could be quoted, planned, and repeated.

Early Numerical Control Milestones

The history of CNC milling begins with pressure from the aerospace industry to machine repeatable curved forms. In the late 1940s, the need for coordinate calculation for rotor-blade geometry triggered the concepts of numerical control. Punched media provided a way to store numeric instructions in a format that machines could read consistently.

Collaboration between early computing pioneers and machine-tool experts pushed the concept from theory to reality. Work tied to U.S. Air Force needs and MIT’s Servomechanisms Laboratory is commonly cited as a turning point toward a demonstrated numerically controlled milling platform. This phase is important because the milling machine became the proof vehicle for closed-loop motion control and repeatable toolpath execution.

These early systems were large, expensive, and difficult to change compared to modern CNC. Hardware logic and punched tape made revisions slow, limiting flexibility for general job shops. Those constraints explain why the later transition to a “computer on the machine” was a practical turning point.

Major Timeline Checkpoints

|

Period / cue |

Milling-control milestone |

What changed for CNC milling workflows |

|---|---|---|

|

Late 1940s |

Coordinate calculation + punched media concepts |

Numeric toolpaths became feasible for complex contours |

|

Early 1950s |

Demonstrated NC milling platforms |

Axis motion followed instructions more repeatably |

|

Late 1950s |

Patents and commercialization efforts |

NC/CNC concepts began moving from labs to industry |

|

Late 1960s–80s |

Broader uptake and improved controller usability |

CNC became a realistic tool beyond aerospace |

|

CAD/CAM era |

Design-to-code workflows reduced manual programming |

Programs became easier to create, revise, and reuse |

The timeline table is intentionally cautious about “first” labels. Claims of the “first” vary by definition, such as the first NC, first CNC, first prototype, or first commercial machine. Verification should rely on the specific definition used in a given source.

Transition from NC to CNC

The NC-to-CNC transition is the key turning point in CNC milling history. Controller architecture changed how milling programs were stored and modified. Early NC controls used hardwired logic and external media, making edits slow and prone to errors. CNC controllers made edits faster by storing programs in memory and allowing on-machine changes.

Microprocessor-era controllers helped CNC milling spread by reducing controller size and improving capability. Shops could run more complex routines and handle more program logic without rewiring control circuits. Direct Numerical Control also supported multi-machine shops when centralized computing was the only practical way to manage programs.

Programming language standardization is also part of CNC milling history because code became a portable way to describe tool motion. Many CNC machines use cnc milling code like G-code for coordinated moves and speeds, while M-codes control auxiliary functions like coolant and tool changes. Controller dialects vary, so always validate programming statements against the specific control manual.

NC vs CNC in Practical Terms

|

Decision dimension |

Numerical Control (NC) in milling |

Computer Numerical Control (CNC) in milling |

|---|---|---|

|

Program storage |

External media like punched tape |

Stored digitally in controller memory |

|

Edit workflow |

Physical edits are slow and error-prone |

On-machine editing is practical |

|

Capability growth |

New functions require hardware changes |

New functions added via software upgrades |

|

Shop scalability |

Program distribution is difficult |

Program reuse and distribution is a normal workflow |

This comparison avoids “better” claims without context. The better choice in a given era depended on cost, availability, and the parts being made. The practical point is that CNC controllers reduced friction in program management, which helped broader adoption.

Machine Evolution and Integration

CNC milling history includes the evolution of machines, as axis capability and automation changed how many setups a part required. Three-axis milling was the baseline for decades, covering a wide range of prismatic parts. Additional rotary axes reduced re-clamping and enabled more complex surface access in fewer setups.

Automation is important in the CNC milling story because it changed the economics of unattended operation and repeat work. Automatic tool changing reduced non-cut time and made mixed-feature programs more practical. Palletized workflows and repeatable fixturing reduced setup variance between batches.

Integration features also shaped modern expectations for CNC milling. Probing and in-process measurement can support setup verification and tool-offset adjustments, but outcomes depend on calibration and training. Connectivity and shop data collection can improve visibility into utilization, but results depend on how a shop uses the data to find and fix bottlenecks.

Adoption Patterns and Impact

CNC milling adoption grew beyond aerospace because more industries needed repeatable accuracy, faster iteration, and complex geometry. Aerospace remained a major driver because its parts reward repeatability and traceable process control. The automotive and industrial equipment sectors benefited from repeat machining of fixtures, molds, and production components.

The medical and electronics industries also pushed CNC milling demand, as small features and complex housings often require milling flexibility. Prototype cycles shortened when programs could be revised quickly, especially as CAD-to-code workflows reduced the burden of manual calculation. The most important adoption driver was not a single metric but the combination of repeatability, programmability, and process documentation.

Explanations often discuss “when CNC became popular,” but popularity depends on the definition. Some accounts note earlier uptake in the late 1960s, while others emphasize later growth when CNC became more affordable and user-friendly. A safe reading treats adoption as a multi-decade expansion, not a single year.

Conclusion

CNC milling history is a practical map of how numerical control, controller computing, and CAD/CAM workflows combined to create modern milling capability. The key story is not that “machines became precise,” but that “milling became programmable, repeatable, and easier to revise.” Readers who keep NC, CNC, and CAD/CAM as separate milestones will make fewer timeline mistakes and better interpret “first” claims.For readers who want to compare sources side by side, exploring cnc milling online can help you cross-check definitions and timelines without relying on a single “first” claim.

At Yonglihao Machinery, we use CNC milling daily for prototype and production work, so we view its history as an operator-facing logic chain, not nostalgia. We recommend using the history as a checklist for assumptions: control architecture, code workflow, setup strategy, and verification method. When a decision depends on CNC capability, the safest approach is to verify controller limits before finalizing the plan.

FAQ

When was CNC milling invented?

Early CNC milling milestones are commonly described in the early 1950s, with MIT-associated demonstrations often cited around 1952. The underlying numerical control concepts are also described as emerging in the late 1940s. “Invented” should be verified by its definition, such as concept, prototype, or commercial system.

Who invented CNC milling?

Many accounts credit John T. Parsons for foundational numerical control concepts tied to aerospace needs. Other accounts emphasize MIT researchers who demonstrated and advanced controlled milling platforms. A precise answer should separate “concept origin” from “demonstrated machine system.”

What existed before CNC milling?

Numerical Control (NC) systems existed before CNC, using punched media and hardware logic without a computer-based controller. Manual milling and earlier machine tools also existed long before NC, but those machines did not execute coordinate programs. A clear answer should distinguish manual tools from numerically controlled ones.

What is the difference between NC and CNC?

NC milling follows numerical instructions but typically lacks the flexible, computer-based program storage and editing workflow of CNC. CNC milling uses a computer-based controller that stores programs digitally and supports easier revisions. The practical difference is in how quickly a shop can revise and reuse programs.

What programming language do CNC mills use?

Many CNC mills use G-code for axis motion and M-codes for auxiliary machine actions, but code dialects differ by controller. The safest practice is to validate program statements against the specific controller documentation. CAD/CAM systems often generate code, but post-processing settings still need verification.

When did CNC milling become widely used?

CNC milling adoption expanded over decades as controllers improved and costs declined. Many explanations point to broader uptake from the late 1960s through the 1980s, with later acceleration as usability improved. The most defensible approach is to treat “popular” as a multi-decade transition rather than a single year.