In metal processing, a common problem exists. Materials strong enough for service are often hard to form, bend, or machine. Annealing is a key heat treatment that solves this issue. It involves heating a metal above its recrystallization temperature but below its melting point. Then, the metal is cooled in a controlled way. This process softens the material, restores its flexibility, and relieves internal stresses. As a result, forming, stamping, and machining become more stable and predictable.

For manufacturers, annealing is a practical tool. It helps avoid cracking, reduce tool wear, and stabilize dimensions. Whether you are planning traditional workflows or adopting CNC turning online solutions, understanding annealing is also important. Knowing when and how to specify it can directly affect cost, quality, and delivery time.

What Annealing Does to Metals?

Quick Definition and Main Purpose of Annealing

Annealing is a heat treatment for metals and alloys. It changes their internal structure to lower hardness, increase flexibility, and reduce internal stress. In practice, a workpiece is heated to a target temperature. This temperature is above its recrystallization point. It is held there for a set time, then cooled at a controlled rate. The cooling usually happens in the furnace or in the air.

The main purposes of annealing are:

- Reverse the effects of work hardening from cold forming, bending, drawing, or rolling.

- Restore flexibility and toughness. This allows the material to be formed or machined further without cracking.

- Relieve internal stresses that build up during rolling, welding, casting, or machining.

- Improve electrical and magnetic properties in materials like copper and aluminum.

Kefore vs. After Annealing

At a high level, the effects of annealing can be seen in these property changes:

|

Material Property |

Before Annealing |

After Annealing |

|---|---|---|

|

Hardness |

High (work-hardened) |

Reduced, more uniform |

|

Ductility |

Low (prone to cracking) |

Increased, better formability |

|

Internal Stresses |

Significant, non-uniform |

Greatly relieved or minimized |

|

Machinability |

Poor, higher tool wear |

Improved, smoother cutting |

|

Grain Structure |

Distorted, elongated |

Recrystallized, more equiaxed |

These changes come from shifts in the metal’s internal structure. They are not just the result of simple heating and cooling.

How Annealing Works at the Microstructure Level

Work Hardening, Dislocations, and Internal Stresses

When a metal is cold-rolled, bent, or stamped, its grains are stretched and distorted. At the atomic level, the number of defects, called dislocations, increases. This is why the material gets harder and stronger. But it also loses its flexibility and becomes more likely to crack.

At the same time, internal stresses get locked into the material. Different areas want to expand or contract but are held in place by each other. These stresses can cause parts to warp during machining or even crack later in service.

The annealing process gives atoms enough heat energy to move and rearrange. Dislocations are removed or organized into lower-energy patterns. New, stress-free grains form. As a result, the material’s properties return to a more balanced and stable state.

Three Stages of Annealing

The annealing process generally has three stages, though heat cycles can vary by alloy.

- Recovery: In this first stage, the material is heated to a moderate temperature. Atoms can move more easily. This allows some dislocations to rearrange and partly relieves stress. Electrical and thermal conductivity may improve. However, the overall grain structure does not change much, and hardness only drops slightly.

- Recrystallization: Next, the metal is heated above its recrystallization temperature, but still below melting. New, strain-free grains start to form and grow. They replace the deformed, work-hardened structure. This stage causes the biggest drop in hardness and the largest increase in ductility.

- Grain Growth: If the metal stays at a high temperature for too long, or cools very slowly, grain growth occurs. Existing grains get larger as smaller grains disappear. This can make the material even more flexible, but too much growth can reduce its strength and toughness. Controlling time and temperature here is key to balancing formability and performance.

Types of Annealing

Different annealing processes are used for specific materials and desired results.

Full Annealing

Full annealing is often used for carbon and alloy steels. It is for parts that need to be as soft and uniform as possible. The steel is heated above its upper critical temperature to form a structure called austenite. It is held long enough for the change to be uniform. Then, it is cooled slowly in the furnace.

This process:

- Creates a fairly coarse but uniform structure with low hardness.

- Maximizes flexibility and machinability, which is useful before heavy forming or machining.

- Is common for forgings, castings, and thick sections that need more processing.

Process Annealing

Process annealing, or subcritical annealing, is mainly for low-carbon steels that have been cold-worked. The material is heated to a temperature below the critical point. It is held for a short time and then cooled in the air.

Typical goals are to:

- Restore enough flexibility for the material to undergo more cold forming.

- Reduce the forces needed for forming and lower the risk of cracking.

- Provide a practical “intermediate softening” step in multi-stage forming processes.

Normalizing

Normalizing is a separate heat treatment, but it is often discussed with annealing. The material is heated slightly above the upper critical temperature. It is then cooled in still air instead of in the furnace.

Compared with full annealing:

- Normalized steels are usually stronger and harder, but a bit less flexible.

- The air-cooling rate creates a finer and more uniform grain structure.

- It is widely used for structural steels where uniform properties and stability are important, but maximum softness is not needed.

Stress-Relief and Recrystallization Annealing

Stress-relief annealing heats the material below its critical range. It is held at that temperature to let internal stresses relax, then cooled slowly. This is used after welding, casting, or heavy machining when dimensional stability is key.

Recrystallization annealing is for cold-worked materials. The workpiece is heated just above its recrystallization temperature. This allows new, strain-free grains to form without changing phases. This treatment:

- Lowers hardness more than simple stress relief.

- Restores a more uniform grain structure.

- Is common for cold-rolled sheets and cold-drawn bars.

Other Specialized Annealing Methods

For some alloys and tool steels, more specialized annealing processes are used:

- Isothermal annealing: The metal is heated, then cooled quickly to a lower temperature. It is held there to get a more controlled structure and better machinability.

- Spheroidizing annealing: This is used for high-carbon steels. It changes hard carbides into a round shape. This greatly improves machinability and formability before the final hardening step.

These methods are chosen when standard annealing cannot provide the needed properties.

What Metals and Parts Benefit Most from Annealing?

Carbon and Alloy Steels

Most carbon and low-alloy steels respond well to annealing. Typical situations include:

- Forgings or castings that need full annealing before precision machining.

- Cold-rolled or cold-drawn parts that are too hard to bend or punch.

- Stamped parts that need more forming without cracking.

For these materials, the choice between full annealing, process annealing, and normalizing depends on the final goals.

Stainless Steels, Tool Steels, and Heat-Resistant Alloys

These materials also undergo annealing, but their behavior is more complex:

- Some stainless steels are annealed mainly to restore corrosion resistance, not just to soften them.

- Tool steels may need spheroidizing to improve machinability before hardening.

- Heat-resistant alloys often need special furnace atmospheres to avoid surface damage.

For these materials, it is vital to follow alloy-specific guides instead of using a generic cycle.

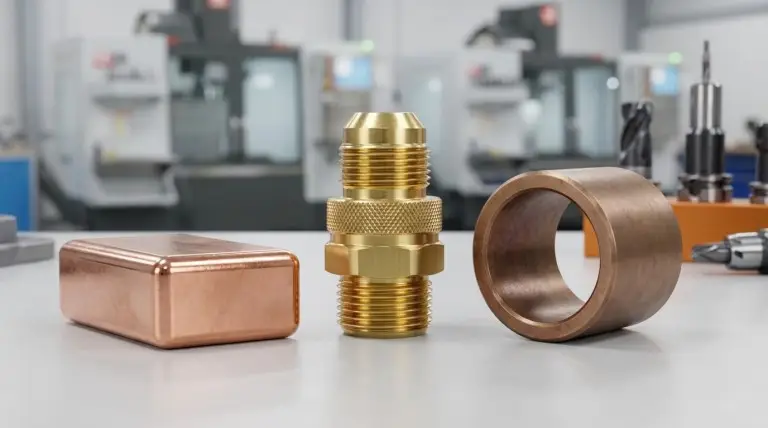

Copper, Brass, and Aluminum

Metals like copper, brass, and aluminum are often annealed to:

- Recover flexibility after wire drawing, bending, or deep drawing.

- Improve electrical conductivity by reducing internal defects and stresses.

- Allow for sharper bends and more complex shapes without tearing.

For example, annealed copper and aluminum are common in electrical parts where both formability and conductivity are important.

Temperature, Time, and Cooling Control in Annealing

Heating Stage

Successful annealing requires heating to the right temperature and holding it long enough.

- If the temperature is too low, only partial recovery happens. Hardness and stress remain.

- If it is too high, unwanted grain growth can occur, reducing toughness.

Soaking time depends on the part’s thickness, the alloy, and the furnace. Engineers choose a temperature and time that ensure full recrystallization without making the grains too large.

Cooling Strategies

The cooling stage directly affects the final structure and properties:

- Furnace cooling (very slow) is used for full annealing. It maximizes softness and minimizes thermal stress.

- Air cooling is used for normalizing and some stress-relief cycles. It gives a balance of strength and flexibility.

- Some non-ferrous metals may be cooled in water or oil, depending on the needed properties.

Choosing the right cooling method helps control hardness, distortion, and stress.

Furnace Types and Atmosphere (Air, Protective Gas, Vacuum)

Annealing can be done in different furnace environments:

- Air furnaces are common for general steels, but surfaces can oxidize.

- Protective atmosphere furnaces (e.g., using nitrogen) reduce oxidation. They are used when surface finish is critical.

- Vacuum furnaces are best for high-value alloys where surface quality is essential.

The right furnace and atmosphere help control surface quality and finishing costs.

Benefits and Trade-Offs of Annealing in Production

Improved Ductility, Machinability, and Electrical Properties

Well-planned annealing offers several benefits:

- Higher flexibility and toughness, reducing the risk of cracking.

- Better machinability, smoother cutting, and less tool wear.

- For copper and aluminum, improved electrical properties.

- More uniform and predictable behavior in stamping, bending, and welding.

In many cases, annealing makes it possible to use stronger or more difficult materials without high scrap rates.

Time, Energy, and Possible Strength Loss: The Limitations

Annealing also has clear trade-offs:

- It takes time, especially for thick parts and furnace cooling.

- It uses energy and requires furnace capacity, which adds to production costs.

- Poorly controlled annealing can lead to large grains and strength loss.

For this reason, annealing should be a deliberate process step with clear goals.

Practical Applications and Case Examples in Metal Processing

Sheet Metal, Wire, and Deep-Drawn Parts

Cold-rolled sheet, drawn wire, and deep-drawn parts are classic examples for annealing.

- After heavy cold working, sheet and wire become hard and brittle. Annealing restores their flexibility for more forming.

- Deep-drawn aluminum or brass parts often need annealing between steps to prevent tearing.

In these cases, annealing directly affects whether the parts can be formed without cracks.

Welded Structures

Welding creates intense heat and stress changes around the weld area, or heat-affected zone (HAZ). Stress-relief annealing after welding:

- Reduces internal stresses to minimize distortion and cracking.

- Helps restore more uniform properties in and around the weld.

This is especially important for thick sections and parts with tight dimensional tolerances.

Before CNC Machining, Stamping, or Bending

For some materials, it is cheaper to anneal first, then machine or form.

- Very hard or work-hardened materials cause severe tool wear in CNC machining.

- Complex bends in stamping may not be possible without first softening the material.

Planning to anneal before these operations can reduce scrap, stabilize dimensions, and extend tool life.

Quality, Tolerance, and Common Problems in Annealing

Typical Quality Targets

A quality annealed part is not just “softer.” It is controlled.

- Hardness should be within a specific range.

- The grain structure should be uniform and not too coarse.

- Distortion must be within tolerance, especially for long or thin parts.

These targets should be agreed upon by the designer, buyer, and supplier.

Common Mistakes (Underheating, Overheating, Uneven Cooling) and How to Avoid Them

Typical problems in annealing include:

- Underheating or short soak time: Stresses remain, hardness is too high, and parts crack.

- Overheating or long hold time: Grains grow too large, reducing strength.

- Uneven heating or cooling: Distortion, warping, and leftover stress pockets occur.

Good furnace calibration, proper loading, and process checks are key to avoiding these issues.

Simple Selection Guide

Quick Checklist for Designers and Buyers

You should consider an annealing step if:

- The material is too hard from cold-working and cracks during forming.

- You need tight dimensional tolerances after welding, casting, or heavy machining.

- Tool wear and machining problems are too high.

- The part must be formable yet have stable properties.

If several of these apply, it is worth discussing annealing with your supplier.

When Annealing Is Not Recommended or Can Be Replaced

Sometimes, annealing is not the best choice:

- When high strength is the main goal, and a different heat treatment is better.

- When normalizing alone achieves the needed properties.

- When cost and time do not justify a full annealing cycle.

The choice depends on the material, part shape, load conditions, and overall process.

Yonglihao Machinery: From Annealed Blanks to Finished Parts

Founded in 2010, Yonglihao Machinery focuses on precision metal stamping, CNC machining, and laser cutting. In many projects, we work with annealed or stress-relieved materials. We also integrate heat treatment partners to ensure stable forming and machining.

By combining the right heat treatment with controlled operations, we help customers get more reliable quality, longer tool life, and predictable delivery.

FAQ

When should I consider annealing my parts?

Consider it when cold-working makes material too hard, or when welding introduces high stress. Also, use it if you see cracking during forming or machining. If forming forces are high and scrap rates are rising, annealing is often a good solution.

Can all metals be annealed the same way?

No. Steels, copper, and aluminum all respond to annealing, but each needs a specific temperature, time, and cooling method. Special alloys like stainless steels and tool steels require even more precise control.

What is the difference between full annealing, process annealing, and normalizing?

Full annealing heats steel above its critical temperature and cools it slowly in a furnace for maximum softness. Process annealing heats below the critical range to restore some flexibility. Normalizing heats above the critical range and air cools for a finer structure and higher strength.

Will annealing always reduce strength and hardness?

It generally does, but how much depends on the process. Full annealing gives the most softening. Other methods like stress relief can balance strength and flexibility. The key is to choose a treatment that matches your needs.

Does annealing add much time and cost?

It adds furnace time and energy costs, so it does increase cost and lead time. However, it often reduces scrap, stabilizes machining, and extends tool life. These savings can offset the extra process cost.

How should I specify annealing on drawings?

Indicate the process type (e.g., full annealing), target hardness range, and any critical distortion limits. For key parts, add notes on furnace atmosphere or inspection methods to align expectations with your supplier.