Thread tapping seems simple. But in real machining, it can easily ruin a good part or delay a prototype. The same hole, drilled in the same setup, can succeed or fail. The outcome often depends on using the right type of thread tap.

At Yonglihao Machinery, we do a lot of CNC prototyping and small-batch machining. We see this issue every day. This guide covers the main types of thread taps. It explains how they are used and how to pick the right one for your job.

What Is a Thread Tap ?

A thread tap is a tool that cuts or forms threads. It works inside a pre-drilled hole so that screws and bolts can fit. In metalworking, good threads are vital for strong, compact, and repeatable joints.

Using the wrong tap for the material and hole might still create a thread. However, the risk of breakage is higher. The fit might be poor, and you may need more rework. Knowing the basic tap categories is a key part of process planning, not an optional detail.

Key Parts and Materials of a Thread Tap

All thread taps have a few key parts. These parts control how they cut, guide, and clear chips. The body is the threaded cutting section. Its front chamfer has tapered threads that slowly cut into the workpiece. The remaining full threads guide the tool and size the finished thread.

Flutes, or grooves, run along the body. They provide cutting edges, space for chips, and a path for lubricant. Between the flutes are the lands, which support the cutting edges. The heel is the relieved area behind the land that lessens friction and rubbing.

Above the body is the smooth shank. It has markings for thread size, pitch, and thread form. Many taps have a square tang at the top. This driving end lets the tap be held in a wrench or machine holder without slipping.

Tap markings show the nominal size and pitch (like M8×1.25 or ¼-20 UNC). They also show the thread form code (metric, UNC/UNF, NPT), tap material (HSS, HSS-Co, carbide), and class of fit. Reading these markings tells you exactly what thread you will cut.

The tap’s material is as important as its shape for performance and life:

|

Tap Material |

Durability |

Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

|

Carbon steel |

Medium |

Light duty, soft metals |

|

HSS (High-Speed Steel) |

High |

General metal processing |

|

HSS-Co / Cobalt HSS |

Higher |

Tough alloys, stainless steels |

|

Solid carbide |

Very high |

Abrasive or hard materials, high-volume CNC |

In practice, you always choose a mix of geometry and material, not one alone.

Main Types of Thread Taps and Their Typical Uses

This section groups the main types of thread taps by their shape and chip control. It shows which hole types and materials they suit best. Matching your job to these groups helps you find the right tap quickly.

Taper Hand Tap

A taper hand tap has a long chamfer with about 8–10 tapered threads. It enters the hole gradually and cuts with a low load. This makes it a good starting tap for tough materials or when alignment is not perfect.

The downside is that it cannot finish a thread to full depth in a blind hole. It is also slow if used alone. A plug or bottoming tap usually follows it.

Plug Hand Tap

A plug hand tap has a medium chamfer of about 3–5 threads. It balances easy starting with the ability to cut deeper. It is the most common “general-purpose” thread tap for daily work.

You can use plug taps alone in through holes and many shallow blind holes. But they may not finish the last threads at the bottom of a deep blind hole.

Bottoming Hand Tap

A bottoming hand tap has a very short chamfer, with just 1–2 tapered threads. Its cutting edges reach full diameter almost at once. It is the best choice for finishing the last threads at the bottom of a blind hole when you need full engagement.

A bottoming tap does not remove material slowly, so it should not be the first tap used. It works best after a taper or plug tap has already formed most of the thread.

Spiral Point Tap

A spiral point tap is often called a gun tap. It has straight flutes but a special front cutting edge. This edge pushes chips forward in the feed direction. This allows higher cutting speeds and smooth chip flow in through holes. It is a standard choice for high-speed machine tapping.

Because chips are pushed ahead, spiral point taps are not good for deep blind holes. Chips will pack at the bottom and jam the tap.

Spiral Flute Tap

A spiral flute tap has helical flutes like an end mill. These flutes pull chips back out of the hole toward the top. This chip-lifting action makes it the best tap for blind holes. It is especially useful in soft materials that form long chips.

Spiral flute taps also work well in interrupted holes, like cross holes or keyways. They cost more than basic hand taps and their cutting edge is a bit weaker. They are usually saved for jobs where chip control is important.

Extension Tap

An extension tap is a hand or machine tap with a very long shank. It can reach holes deep inside a bore, recess, or pulley hub. You choose it when a standard tap would hit other features before reaching the thread location.

The long shank makes the tap less stiff, so you must control feed and torque. Cutting aggressively with extension taps raises the risk of bending or breaking.

Machine Tap

A machine tap is made for power-driven or CNC tapping. Its shape, core thickness, and coatings are optimized for good chip control and long life. It can run at higher speeds with better results than basic hand taps.

Machine taps work for both blind and through holes if you pick the right version. This could be a spiral point or spiral flute type. They are the default choice for production threading in many shops.

Thread-Forming Tap

A thread-forming tap, or roll tap, does not cut metal. It cold-forms the thread by moving material. No chips are made, so tapping is cleaner. Tap breakage from packed chips is greatly reduced.

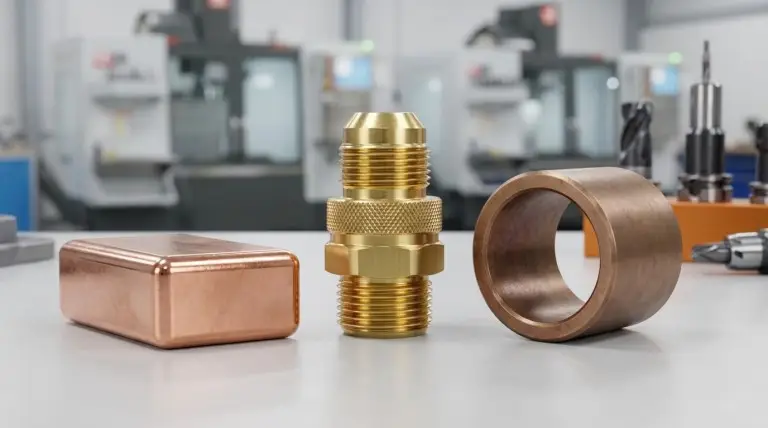

Form taps are great for soft materials like aluminum, copper alloys, and mild steels. They often make stronger threads due to work hardening. They need a larger pre-drill size than cutting taps. They are not suited for brittle or very hard materials.

Pipe Tap

A pipe tap creates pipe threads like NPT or BSPT. These threads are usually tapered to make a pressure-tight seal. These taps remove more material near the top of the hole than at the bottom. They work harder than straight-thread taps.

Pipe taps are needed for hydraulic, pneumatic, and plumbing connections. They require the correct pilot drill and careful depth control. This avoids oversizing the thread and hurting the seal.

Combined Drill-and-Tap Tool

A combined drill-and-tap tool has a drill point at the front and a tap section behind it. This lets the machine drill and then tap in a single cycle. It removes the need for a tool change. It also lowers the risk of misalignment between the two steps.

Each tool works for only one hole size and thread, so it is not flexible. It is also less suited for very deep holes or very difficult materials.

Solid Carbide Tap

A solid carbide tap is made fully from carbide. This gives it very high hardness and wear resistance. It is used for abrasive materials like cast iron or glass-fiber plastics. It is also used for high-volume CNC work where long tool life is key.

Carbide taps are more brittle than HSS. They need rigid setups, exact alignment, and stable cutting. In flexible or poorly aligned machines, they break more easily than HSS or cobalt taps.

Interrupted Thread Tap

An interrupted thread tap has teeth only on every other thread. This leaves spaces that help break chips. It also gives extra room for lubricant and chip removal. This design is useful in sticky materials where normal taps get packed with chips.

Fewer teeth share the load, so these taps may be slightly less rigid. They are usually saved for problem materials, not for general use.

|

Tap Type |

Best For |

Hole Type |

Chip Flow Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Taper hand tap |

Starting by hand, tough jobs |

Blind/Through |

Stays in flutes |

|

Plug hand tap |

General hand tapping |

Through/Blind |

Stays in flutes |

|

Bottoming hand tap |

Finishing blind holes |

Blind |

Stays in flutes |

|

Spiral point tap |

High-speed machine tapping |

Through |

Pushed forward |

|

Spiral flute tap |

Blind, interrupted holes |

Blind |

Pulled upward |

|

Extension tap |

Deep/recessed threads |

Both |

Depends on flute type |

|

Machine tap |

Power/CNC tapping |

Both |

Optimized by design |

|

Thread-forming tap |

Chip-free threads |

Mostly through |

No chips |

|

Pipe tap |

Pressure-tight pipe joints |

Mostly blind |

Varies |

|

Drill-and-tap combo |

Cycle-time reduction |

Mostly through |

As per tap section |

|

Solid carbide tap |

Hard/abrasive materials |

Both |

As per geometry |

|

Interrupted thread tap |

Difficult chip-forming materials |

Both |

Improved chip breaking |

How to Choose the Right Thread Tap for Your Job

To pick the right thread tap, start with four basics. Consider the workpiece material, hole type, thread specification, and production volume. For soft materials like aluminum, a thread-forming tap or a sharp spiral flute tap often works best. For stainless steels or strong alloys, you may need coated machine taps or solid carbide taps to handle the torque and wear.

The hole type helps narrow your choices. For through holes, spiral point taps are usually the most efficient. They push chips forward and out of the way. For blind holes, spiral flute taps help remove chips. A series of taper, plug, and bottoming hand taps can also work to finish the thread.

Thread size and pitch affect the tap’s stiffness. Large, coarse threads allow for stronger taps and faster cutting. Very small or fine-pitch threads need precise alignment and stable feeds. Last, decide if this is a repair, small batch, or large production job. Then choose the tap grade and cost level that fits.

A simple checklist before you tap a thread:

- ✅ What material am I threading (hard, soft, abrasive)?

- ✅ Is the hole blind or through, and how deep is it?

- ✅ What thread size, pitch, and tolerance class do I need?

- ✅ Is this a one-off, small batch, or high-volume job?

- ✅ Can I provide good lubrication and chip removal?

Answering these questions will guide you to the right tap for your task.

Best Practices for Using Thread Taps and Avoiding Breakage

The best way to prevent broken taps is to use the right tap with the right setup. This means correct alignment, feed, speed, and lubrication. Always check that the drilled hole is the right size and is straight. A hole that is too small or crooked will overload the tap right away.

When hand tapping, keep the tap straight with the hole. Apply steady force and turn it back a quarter turn now and then to break chips. In machine tapping, use the cutting data recommended for the tap and material. Do not use a “one-size-fits-all” speed.

Cooling and lubrication are very important, especially in tough materials. Use a cutting fluid or tapping oil made for the material. For example, use soluble oil for carbon steels and low-viscosity oil for aluminum. Good lubrication lowers friction and heat. It also improves the thread finish and extends tap life.

Common thread tapping problems and quick fixes:

- Tap breakage: Check the drill size, setup, and cutting data. This is often caused by the wrong hole size, poor alignment, a bad tap choice, or no lubrication.

- Poor thread finish: Inspect the tap and improve chip removal. This is often due to a worn tap, the wrong tap material, or packed chips.

- Chip packing in blind holes: Switch to spiral flute or thread-forming taps. Clear chips more often. This is common with spiral point taps in blind holes.

For tough materials, check taps often. Reduce speed slightly as tools wear and add more lubrication. Peck tapping cycles in CNC programs can also help clear chips from deep blind holes.

Conclusion

In short, good thread tapping requires the right tap type, material, and cutting conditions. Once you know how different taps work in various holes and materials, picking the right one becomes a clear choice, not a guess.

This matters even more for prototypes and small batches. There is usually only one chance to get a threaded hole right. At Yonglihao Machinery, our engineers use these same principles to select taps. We then test them on the real material before starting a production run.

Whether you tap threads yourself or use a shop, using the right tap saves time and money. It gives you more reliable parts. If your custom parts have tricky threads, a partner like Yonglihao Machinery can help. We understand tap selection and can help you get from a drawing to a working part with fewer problems.

FAQ

What is the difference between a taper, plug, and bottoming tap?

The difference is their chamfer length. A taper tap has the longest chamfer and is for starting threads gently. A plug tap has a medium chamfer and is for general use. A bottoming tap has a very short chamfer. It is used last to finish threads at the bottom of a blind hole.

When should I use a spiral point tap instead of a spiral flute tap?

Use a spiral point tap for high-speed tapping in through holes. It pushes chips forward and out of the part. Use a spiral flute tap for blind or interrupted holes. It pulls chips back toward the top of the hole.

Can I use a hand tap in a CNC machine?

You can use a hand tap in a CNC machine at low speeds, but it is not the best choice. Hand taps are not made for machine speeds or chip control. Machine taps, like spiral point or spiral flute taps, are designed for power tapping.

When should I choose a thread-forming tap instead of a cutting tap?

Choose a thread-forming tap for soft materials. It creates no chips and makes stronger threads. Avoid them in brittle or very hard materials. Always use the correct, larger pre-drill size specified for these taps.

What are the most common causes of broken taps?

The most common causes are the wrong drill size, poor alignment, no lubrication, and using the wrong tap type. To avoid this, check your drill size. Choose a tap that matches the hole and material. Use the right cutting fluid and conservative settings.