Thread milling and tapping both create internal threads, but they behave very differently once you put them on a machine. At Yonglihao Machinery, we choose between them based on four inputs: production volume, material behavior, thread size and depth, and the machine’s capabilities. When cycle time dominates and the thread is standard, tapping often wins. When thread fit control, chip control, or part value dominates, thread milling is usually the safer choice.

This guide explains how each method works, what changes on the shop floor, and the selection rules we use to keep threads consistent. We keep the focus on CNC machining decisions you can apply to real parts. We will not turn this into a full programming class or a thread-standard encyclopedia.

What is thread milling?

Thread milling is our go-to when we need control over thread fit and want a safer failure mode on high-value parts. A thread mill cuts threads by moving in a circular path while advancing in Z to form the helix. Because the tool is milling, we can correct size with offsets rather than swapping tools. If something drifts, we can often bring it back quickly.

We also lean toward thread milling when the material is tough, abrasive, or produces long stringy chips. The cutting action generates shorter chips and typically reduces the “one tool breaks, part is gone” scenario. That matters when the workpiece is expensive or has many operations already completed.

How we form threads

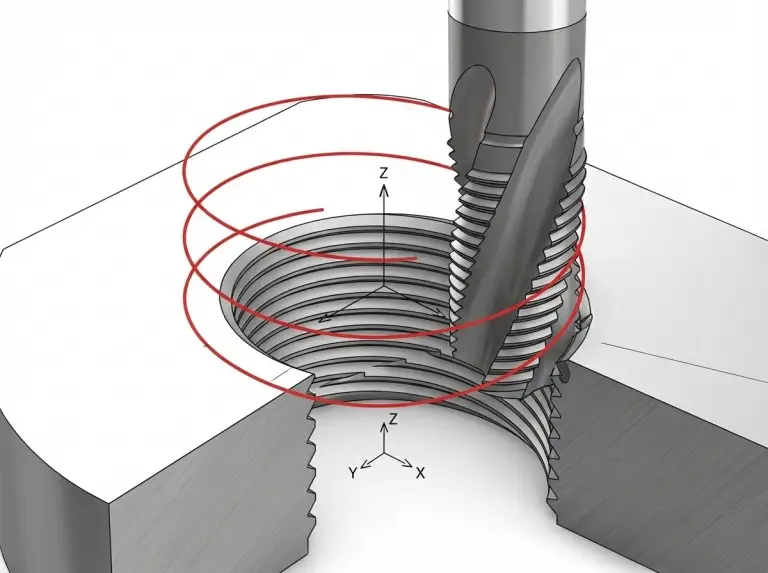

Thread milling forms threads through coordinated tool motion rather than a single dedicated thread-form tool. We first create a pilot hole or bore that leaves room for the thread profile. Then the cutter enters the hole, moves radially to the cutting diameter, and follows a circular path while climbing or descending by one pitch per revolution.

This toolpath is why thread milling is flexible. The tool’s pitch matters, but the thread diameter can often be adjusted within a range by programming and offsets. That flexibility is also why machine rigidity and runout control matter more than many people expect.

Tools we select

We choose the thread mill type based on how much flexibility the job needs and how consistent the geometry must be. Full-profile thread mills generate the full thread form for a specific thread size. They are efficient and tend to produce consistent crest/root geometry for that target size.

Single-profile or single-point style thread mills cut the thread form one feature at a time and can cover a broader range of diameters with the same pitch. They are useful when you want inventory reduction or need unusual diameters. They can take longer because they may require multiple passes or a different strategy to reach full depth.

Tool material is typically carbide for thread mills in modern CNC work. That usually means longer life and more predictable wear than many standard taps. It also means the process responds strongly to toolholding quality and runout.

Machine & holder checks we run

Thread milling demands stable radial cutting. We verify that the setup can resist radial forces without chatter, especially in harder alloys. We pay close attention to runout because it directly affects effective cutter diameter and thread size.

We also verify clearance, because the tool must move in a circular path inside the hole. On small threads, available tool diameters and clearance can become the limiting factor. When threads are extremely small, tapping may be the practical option simply due to tool availability and geometry constraints.

What is Tapping?

Tapping is our first choice when speed and simplicity are the top priorities and the thread is standard. A tap forms the thread in a single pass with a tool that matches the thread geometry. When the machine has rigid tapping capability and the setup is stable, tapping can be very fast and very repeatable.

We also use tapping when the thread is very small or when deep threads are required and the material and chip evacuation are manageable. For small thread sizes, taps are widely available and often easier to apply than tiny thread mills.

How we tap threads?

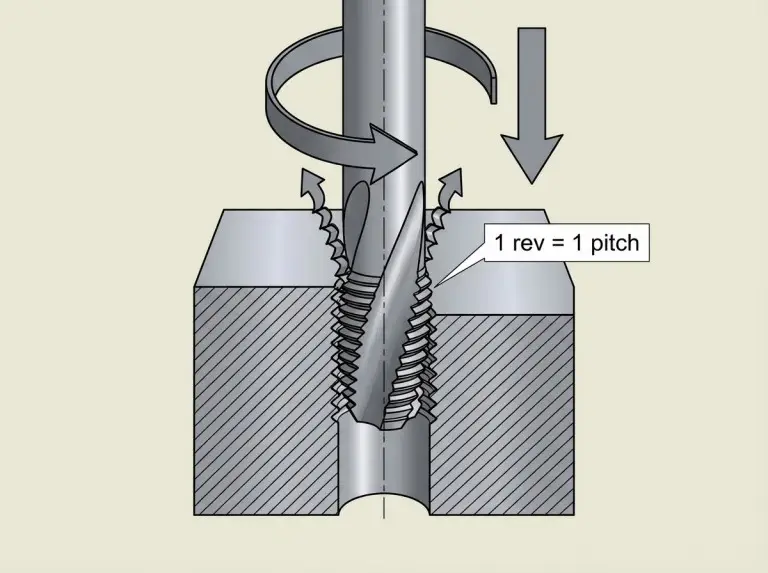

Tapping requires precise synchronization between spindle rotation and feed. The tap must advance exactly one pitch per revolution. If the machine cannot keep that relationship stable, the tap can load up, bind, or break.

Because the tool makes the thread in one motion, torque is a major factor. Larger threads and tougher materials increase torque demand. When torque approaches the machine’s limits or the setup is less stable, thread milling becomes attractive.

Tap choices by job

We select tap style based on hole type and chip behavior. Through-holes often pair well with taps that push chips forward. Blind holes often call for designs that pull chips out, depending on material and depth.

For some ductile materials, forming taps can reduce chip issues because they displace material instead of cutting it. That can improve consistency in the right material, but it also increases forming forces and requires the correct pilot hole size. In materials that do not form well, a cutting tap is the safer path.

We also treat tap selection as material-specific. Geometry and coating choices can change results significantly, especially in stainless steels and other “grabby” alloys. Even with the right tap, lubrication and alignment remain critical.

What our machines must support?

Rigid tapping capability is a practical dividing line. If the control and drive system cannot maintain synchronous motion, tapping becomes less reliable and can require special holders to absorb mismatch. That adds variables and can reduce consistency.

Alignment matters just as much as control capability. Any angular misalignment increases side load on the tap, which increases risk of breakage and poor thread form. If alignment is hard to guarantee due to part geometry or fixturing, thread milling can be the safer choice.

Side-by-Side Comparison

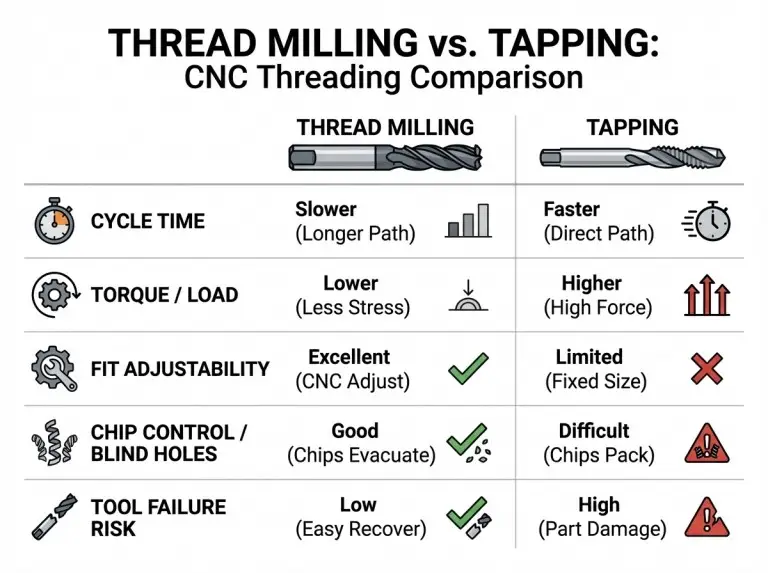

On real jobs, the decision usually comes down to cycle time versus controllability, with part value and scrap risk deciding the tie. Tapping is typically faster per hole, especially when threads are standard and repeated many times. Thread milling is typically more forgiving when you need to adjust fit, control chips, or protect an expensive part.

To make this concrete, we evaluate the same set of factors every time. We keep the comparison focused on outcomes you can measure: throughput, spindle load, thread size control, chip behavior, and tool failure consequences.

Cycle time and throughput

If a job is dominated by threading time and the thread is repeated across many holes, tapping often provides the shortest cycle time. The tool cuts the full thread in one pass. Setup and programming are straightforward on machines designed for rigid tapping.

Thread milling generally takes longer per thread because it requires a circular motion and a controlled helix. The difference may be small on low quantities but becomes meaningful at scale. The tipping point depends on how many holes you are making and how often you would need to stop for tool changes or recover from broken taps.

Torque / spindle load and practical size limits

Taps demand torque, and torque rises quickly with thread diameter and tough materials. If the thread is large or the material is difficult, tapping can push the spindle and drivetrain hard. That can lead to inconsistent results or tool breakage.

Thread milling reduces torque constraints because it removes material gradually. This makes it attractive for larger threads or when the machine is not suited for high torque at low speed. The practical limits for thread milling are more often about tool availability, clearance, and rigidity than raw torque.

Thread fit control and fast correction

Thread milling is strong when thread fit must be tuned. If a thread gauges tight or loose, we can often correct it by adjusting tool offsets, assuming the tool and path are appropriate. This reduces downtime and avoids stocking multiple “nearby” tool sizes for fine adjustments.

With tapping, thread size is mostly “baked in” to the tap geometry. If the result is out of tolerance, the usual fix is to change taps, including size variations, adjust process conditions, or change the hole size. That can be efficient in stable production, but it is less flexible when tolerances are tight or variation is expected.

Chip control, blind holes, and scrap risk

Chip control is one of the biggest practical differentiators. In ductile materials, tapping can generate long chips that pack the flutes, especially in deeper blind holes. That increases torque and raises breakage risk.

Thread milling typically produces shorter chips and gives more control over how chips evacuate. This often lowers risk in deep or blind features, and it can be the safer option when chip packing would scrap a high-value part. If the job is prone to chip trouble, we treat thread milling as a risk-reduction tool.

Tool life and predictability (carbide mills vs common tap materials)

Tool life depends on the specific tool, material, and cutting conditions, but the failure mode matters as much as the average life. When a tap breaks in a hole, salvage can be difficult and the part may be lost. That risk grows with tough materials, deep holes, and marginal alignment.

Thread mills can break too, but the consequence is often less severe. Because the tool is smaller relative to the hole and the process is not wedged like a tap, it may be easier to recover. In addition, thread milling wear can be more predictable in many jobs, which supports stable quality control.

| Decision factor | Thread Milling tends to win | Tapping tends to win |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Mix is high, holes vary, or rework risk is costly | Same thread repeated in high volume |

| Machine load | Torque is a concern or thread is large/tough material | Machine supports rigid tapping and load is manageable |

| Fit control | Thread class/fit needs fine tuning via offsets | Standard fit is acceptable and stable |

| Blind holes & chips | Chip packing risk is high or part is high value | Chips evacuate well and hole type suits the tap |

| Tool failure consequence | Scrap cost is high and recovery matters | Scrap risk is acceptable and uptime is the priority |

Selection Guide by Job Constraints

A reliable selection comes from matching job constraints to the method, not from tool preference. The same part can push you toward tapping or milling depending on volume, inspection requirements, and machine capability. Below are the rules we use most often, with the conditions that can override them.

By material behavior (hardness, toughness, stringy chips)

If the material is tough, abrasive, or tends to produce stringy chips, we usually start with thread milling. The chip control and lower wedging risk help stabilize the process. This is especially true when blind holes are involved.

If the material is more forgiving and chip evacuation is clean, tapping becomes attractive. Ductile materials can still be tapped successfully, but chip control must be managed with the right tap style, lubrication, and hole condition.

By thread size & depth (micro threads, deep threads, large threads)

If the thread is extremely small, tapping often becomes the practical choice because taps are widely available and thread mills may not fit or may be fragile. For micro features, stability and alignment are critical no matter what you choose.

If the thread is very deep relative to diameter, tapping can be efficient when chip evacuation is controlled and the machine can maintain synchronization. If deep threads are paired with tough material and blind holes, thread milling often reduces risk, even if cycle time increases.

If the thread is large, thread milling can avoid torque limitations and reduce breakage risk. Clearance and tool diameter must still be checked, but torque is less likely to be the limiting factor.

By production volume (high-mix/low-volume vs high-volume)

For high-volume production with identical thread features, tapping is often the most efficient method. The per-hole cycle time advantage tends to dominate. The tooling strategy is straightforward once the process is stable.

For high-mix work or frequent changeovers, thread milling often reduces tool inventory and setup time. One tool can cover multiple sizes within a pitch family, and fit adjustments are faster. This is why many prototype and low-volume jobs lean toward thread milling.

By tolerance and functional fit (gaging, class, adjustability needs)

If the thread must meet a tight functional fit and you anticipate needing adjustments, thread milling is usually the safer choice. Offset-based correction is quick and reduces downtime. This is valuable when threads must gauge consistently across small batches.

If the thread is standard and the fit class allows typical variation, tapping is often sufficient and faster. The key is stability: consistent hole size, good alignment, and appropriate lubrication.

By equipment capability (rigid tapping, spindle speed, holder quality)

If your machine supports rigid tapping and maintains synchronization reliably, tapping becomes a strong option. Without rigid tapping, the process can still work, but it adds variables that can reduce consistency.

For thread milling, the machine must be stable and the toolholding must control runout. If runout control is poor, thread size can drift and finish can suffer. When holder quality is limited, tapping may actually produce more consistent threads—if the machine supports it.

Quality & Risk Control

Thread quality is controlled more by basics than by slogans. We treat setup stability, hole preparation, toolholding, and inspection workflow as one system. When threads fail, the root cause is often upstream: wrong hole size, poor alignment, poor chip evacuation, or unstable clamping.

Below are the controls we apply on most jobs, regardless of method.

Toolholding and runout control

For thread milling, runout control is a priority. Excess runout changes effective cutter engagement and can shift thread size. It can also increase tool wear and degrade surface finish.

We also avoid marginal holders that allow micro-movement under radial load. Stable holding reduces chatter and supports consistent thread form. When milling hardened or tough alloys, this stability becomes even more important.

Lubrication/coolant strategy by method

Tapping benefits from strong lubrication because the tool is in full contact and friction is high. Inadequate lubrication can lead to seizing, torn threads, and breakage. We select cutting fluids based on material and tap style and keep the process consistent.

Thread milling often benefits from clean coolant flow to evacuate chips and control heat. The goal is stable cutting conditions and predictable wear. The exact approach depends on the material and the shop’s coolant system, but consistency is the key.

Entry/exit moves to protect first threads and edges

First threads are where many quality issues show up. Poor entry can produce burrs, torn crests, or distorted lead-in threads that fail gauges. We use controlled entry and exit strategies appropriate to the method.

For tapping, alignment and correct hole preparation protect the first threads. For thread milling, a stable approach and exit reduces burrs and protects the top threads. If the part is thin-walled, we pay extra attention to deflection and distortion.

Gaging workflow and correction steps we apply fast

Inspection closes the loop. We confirm the method and settings against the required gauge or measurement approach and then lock in the process. When something drifts, we want a correction path that is quick and predictable.

Thread milling often allows correction by offset changes. Tapping corrections often involve tool changes, hole adjustments, or lubrication/parameter changes. The best workflow is the one that minimizes downtime while protecting the part.

If a tool breaks: salvage probability and safest recovery path

If a tap breaks, the risk of losing the part is higher. That is not always true, but it is common enough that we treat it as a planning factor. The deeper the hole and the tougher the material, the higher the risk.

If a thread mill breaks, recovery can be easier in many cases, but it still depends on the geometry and how the tool failed. The practical takeaway is to match the method to the part’s value and the cost of a failure. On expensive parts, we bias toward methods that reduce catastrophic failure.

Conclusion

The best method is the one that hits your thread requirements with the lowest overall risk and the right cycle time for your production model. At Yonglihao Machinery, we typically use tapping for high-volume, standard internal threads where speed is critical and the machine supports rigid tapping. We typically use thread milling when fit control, chip control, or part value makes adjustability and recovery more important than pure speed.

If you share your material, thread size and depth, hole type, and target volume, we can recommend the most stable threading strategy for your CNC machining project. As a cnc machining service provider, we apply these same selection rules to keep threads gauging correctly from prototype to production.Our goal is simple: threads that gauge correctly, repeatably, and on schedule.

FAQ

What is the primary difference between thread milling and tapping?

Thread milling cuts threads with a helical milling toolpath, while tapping forms the full thread in one pass using a dedicated tap. Milling is more adjustable and often safer on high-value parts. Tapping is generally faster and simpler when the thread is standard and the machine supports rigid tapping.

Which method is better for blind holes?

Thread milling is often safer in blind holes when chip packing is a risk. It typically produces shorter chips and allows more controlled evacuation. Tapping can still work well in blind holes, but it requires the right tap style and consistent lubrication to avoid chip jams and breakage.

Can thread milling create external threads?

Yes, thread milling can create internal or external threads as long as the toolpath and geometry allow clearance. Tapping is primarily an internal-thread method in common CNC practice. If you need external threads with the same general approach, milling is usually the more flexible option.

When should I choose tapping even if thread milling is available?

Choose tapping when you need maximum throughput on repeated standard threads and your machine can perform rigid tapping reliably. Tapping is also often the practical choice for very small thread sizes where thread mills may be limited by clearance or availability. The key is stable hole size and alignment.

How do you adjust thread size if the thread is out of tolerance?

With thread milling, thread size can often be corrected through small offset adjustments, which is fast and reduces downtime. With tapping, corrections usually require changing to a different tap size variant or adjusting the hole size and process conditions. Either way, the correction must match the inspection method used.

Can one CNC machine do both thread milling and tapping?

Yes, many CNC machines can do both, but capability matters. Tapping benefits from rigid tapping functions and stable synchronization. Thread milling benefits from good rigidity, runout control, and the ability to execute consistent helical interpolation.